Here's why young people think oracy may be the answer

New research of more than 5000 young people by Voice 21 provides valuable insight into how oracy-based approaches can help students become more confident – in their learning, their social-emotional development, their self-belief for future prospects, and much more.

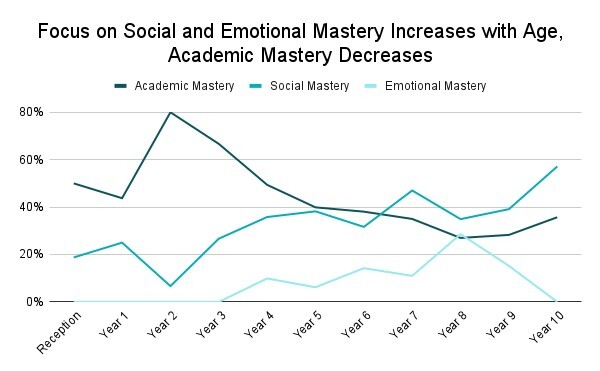

Responses from students aged between 5 and 16 reveal that while younger students are more likely to perceive academic confidence in relation to oracy, older students perceive the confidence they acquire from having good oracy skills in more social and emotional terms.

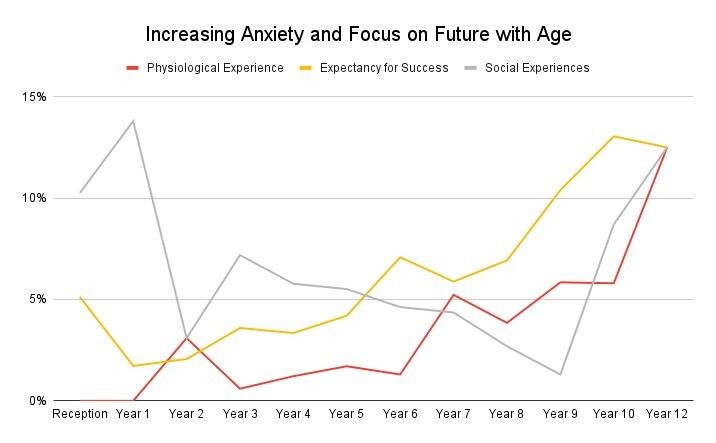

Additionally, the survey outlined that students’ focus on future goals and anxiety around oracy also rises with age.

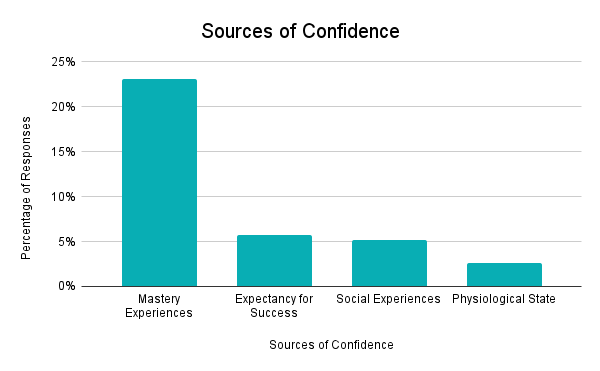

The survey’s 3131 responses were analysed for themes relating to confidence and self-efficacy. Voice 21 identified and labelled these into four coded categories:

Reports of mastery experiences accounted for 23% of all responses. These include responses such as ‘I am getting better at speaking in class,’ or ‘[oracy] helps me pronounce words properly.’ This indicates that students perceive oracy as an asset to their education, and something that makes them feel more confident about their academic progress.

For younger children, academic mastery is the most common experience by a significant margin; academic mastery peaked in Year 2, with 80% of reported mastery experiences categorised as academic (it should be noted, however, that the Year 2 group had a lower number of responses, with a total of 15).

As children get older, their academic mastery experiences decline, hitting their lowest point at Year 8 with 23% of total mastery experiences. Social mastery experiences, however, have a steady upward trend with age, reaching their peak at Year 10 at 57% of total reported mastery experiences for the year group.

Emotional mastery experiences reach their peak at Year 8, at 29% of total reported mastery experiences for the year group. There are a variety of potential reasons for this, including that students’ understanding of oracy and its benefits becomes more nuanced as they get older.

At the same time as we observe an uptick in reports of social and emotional mastery experiences, we also see a jump in reports of anxiety and nervousness in relation to oracy.

Students also report more focus on their future and the ways in which they believe that oracy will help them with their school education, further education, and careers. This trend moves steadily upwards with age and hits a notable spike at Year 9 and Year 10.

Students believe that good oracy skills can provide them with confidence in a variety of areas including academic, social and emotional.

These differing types of confidence can be used to tailor oracy teaching according to student’s age, for example using small group discussions to address the anxiety that some older students feel around oracy, to improve their social and emotional well-being.

© 2024 Voice 21. Voice 21 is a registered charity in England and Wales. Charity number 1152672 | Company no. 08165798